Deconstruction Monogatari —Part Three— Language

Michael Lee

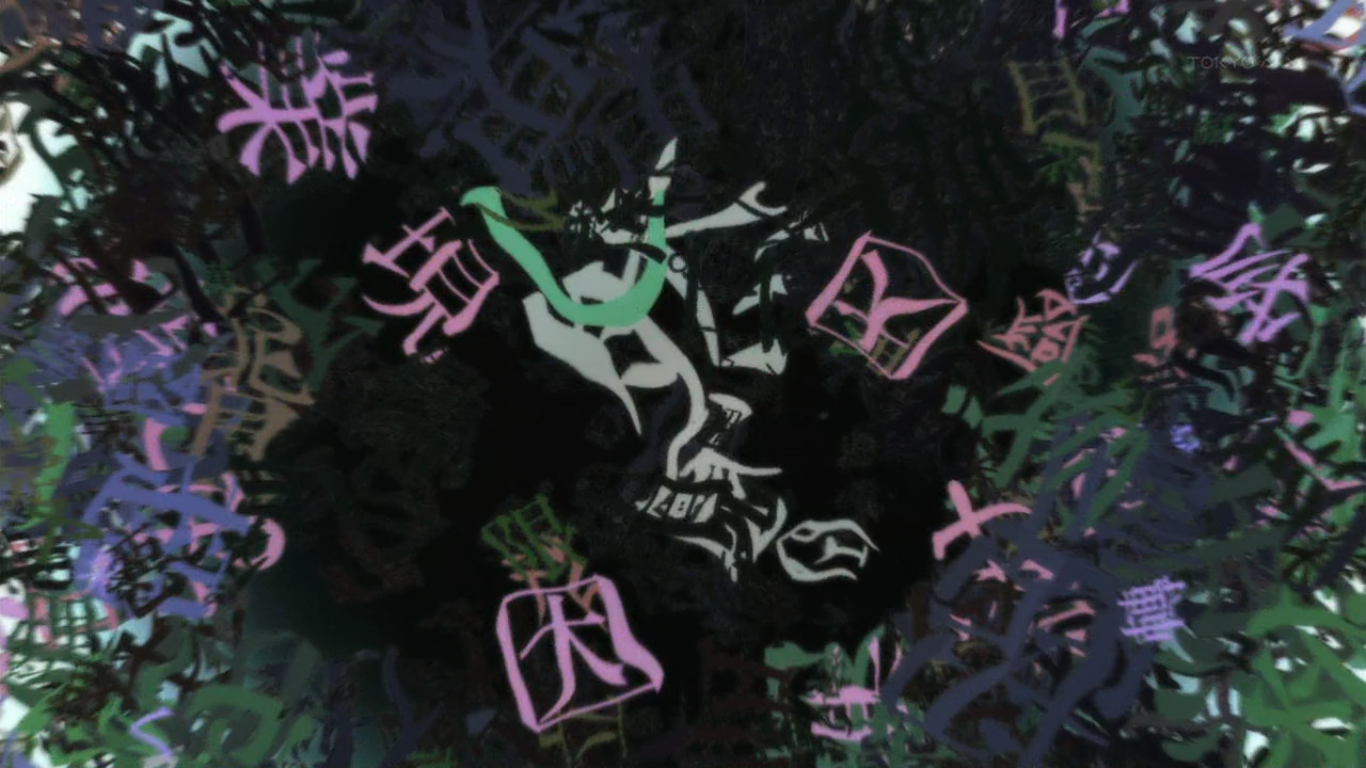

The worst nightmare of any student of Japanese — an indecipherable ball of kanji hurtling towards you.

SHAFT/Aniplex

Deconstructionmonogatari.

—NisiOisiN Palindrome—

其ノ壹

(Part Three)

*In this series of articles we will examine key aspects of the SHAFT adaptation of NisiOisiN's dialogue-heavy Monogatari series of light novels. The anime is helmed by Akiyuki Shinbō, a director with a very distinct style, and the pairing of Shinbō and NisiOisin has created something of a perfect storm of postmodernity.*

Textual Awakening

"a literary engagement with the screen as a surface as well as a window. From this perspective, 'reading the screen' is not simply a process of understanding the visual language of the cinema; it can also be framed in terms of a complex oscillation between viewing (images) and reading (text)." -Kim Knowles

The Monogatari series of light novels make use of clever (or not, depending on your view of NisiOisin's style) wordplay, heavy dialogue, and well-established tropes to drive the series. It should come as no surprise that the anime adaptation could not escape this orbit around the written word, and as such, there is a significant textual element to the anime series. Woven into the series through a number of devices, text becomes a key part of the visual language of the show. In a number of cases in Monogatari, the text is the image, the only visual signifier on the screen.

Monogatari employs intertitles in a number of ways to enhance the story being told. These intertitles can help drive the narrative forward, usually as an epigraph, detailing some thoughts floating around in Araragi's head, which appear to be verbatim from the light novels themselves. The linked intertitle provides the viewer with background information on Araragi Tsukihi (Araragi Koyomi’s little sister) including an explanation on why she’s changed her hair from straight and long to a “shaggy dutch bob.” This information is not revealed elsewhere in the anime. If you want to know about Tsukihi’s new do, only the intertitle delivers. These images flash on the screen at an increasing rate of speed, often reaching a speed too quick for the viewer to read without pausing the video. Another use for the intertitles can be to indicate subtle scene changes. Kuro Scene (black scene) happens when Koyomi blinks, sometimes it even includes a camera shutter sound effect, suggesting a moment being committed to memory. Then there are the Aka Scenes (red scene) which are also blinks, but indicate an intense emotion as well. Attaching a visual language image to a physical action performed by a character integrates text into film, blending the two mediums into one media object.

For the intertitles that are used to present information to the viewer, while it may be seen as a way for SHAFT to cut production costs—and certainly that is possible— if we consider Barthes' Rhetoric of the Image, he sees the flip from image to linguistic message as a technique to "fix the floating chain of signifieds in such a way to counter the terror of uncertain signs." When we're presented with a scene in Monogatari, intertitles present an opportunity to make sense of the scene before us. In the example, the word “dislike” is shown to us during a scene between Koyomi and Hachikuji Mayoi, where Hachikuji is mad at Koyomi for not returning her backpack to her when it was left at his house. This gives us a clear indication of the feeling coming from Hachikuji, when the visuals and dialogue may be rife with uncertain signs.

Given Monogatari's penchant for fantastical visuals that stretch the reality of the anime world in which they are found, text is added to provide information that does not exist in the image, working in concert to arrive at an understandable syntax. Barthes describes this action of "relay" as a "complementary relationship; the words, in the same way as the images, are fragments of a more general syntagm and the unity of the message is realized at a higher level, that of the story, the anecdote, the diegesis." The intertitle regarding Tsukihi’s haircut would be a case of relay, in that the image (and the dialogue of the scene where Tsukihi is seen with the ‘shaggy dutch bob’) gives us no explanation as to how this came about, the intertitle works with the image to complete the picture. The other technique that can be deployed to make sense of images is that of "anchorage" wherein text "directs the reader through the signifieds of the image, causing him to avoid some and receive others; by means of an often subtle dispatching, it remote-controls him towards a meaning chosen in advance." This occurs in Monogatari in cases where the intertitles explicitly provide information about the scene, guiding us to through the field of signifieds in a scene, helping us arrive at an interpretation as intended by the creator of the work. Such as 不憫ナ生キ物 (fubin na ikimono; pitiful creature) being shown to the viewer during a scene where a character tells a sad story about their cursed existence. We should pity Hachikuji as she tells her sob story, there is no other emotion to feel in this case other than pity, the intertitle has told the viewer how to interpret the scene.

This complementary relationship of image and text is further established in Ranciere's future of the image, when we consider his thinking on the clash of heterogeneous elements creating the opening for a common measure. While Ranciere proposes that these elements come at each other in a violent manner, and only through that harsh juxtaposition do you find that common measure, his proposal is nonetheless that only through mashing these different elements together can the effect be achieved. This is what Ranciere calls the dialectic way of achieving a cohesive narrative through heterogeneous elements.

He also proposes another way to reach this cohesive end, and that is through something he calls the symbolist way. Stating that "elements that are foreign to one another work to establish a familiarity, an occasional analogy, attesting to a more fundamental relationship of co-belonging, a shared world where heterogeneous elements are caught up in the same essential fabric, and are therefore always open to being assembled in accordance with the fraternity of a new metaphor" which we could also apply to Monogatari, as the visual language of the series is built on heterogeneous elements working in concert. And only when you take the fast-paced dialogue, the textual elements, the bizarre geography, and the database characters and see them together as part of the "essential fabric" of the series, can a deeper sense of meaning be made from it.

The Visual Language of Manga

Though the intertitles in Monogatari are the most noticeable inclusion of textual elements in the series fabric, we should also consider other ways in which ‘language’ creeps in to this series. If we go back to the origins of anime, the art form was first known as manga eiga or "manga film" and if we look to manga and the visual language present there, we find that anime —and certainly, Monogatari— has retained and deployed the visual language of manga in its own visual language systems.

When we look at manga, the language used meets somewhere at the crossroads of written and spoken language, and linguistic and non-linguistic according to Yoshiko Numata. The visual structures —speech bubbles, backgrounding art—delivering the text can play up textual elements or hide them just off in the periphery in order to create narrative flow. At the time, Numata was focused on onomatopoeia in manga, and those make an appearance in Monogatari. Whether the viewer sees an intertitle for a “sigh” or a representation of the “cold sweat” being felt by Koyomi, the language of manga is present in the Monogatari anime.

Giancarla Unser-Schutz says that both the linguistic (ie. dialogue) and the visual language of a work are need for it to be complete. In manga, she also identifies text that can be identified as "secondary" yet these text types —handwritten lines/thoughts and authorial comments— act as visual clues to allow readers to choose between different interpretations." Positing that the handwritten text and authorial comments "create a sense of community with authors and to those readers desiring one."

Now, with anime, the linguistic is usually taken care of by spoken dialogue, so what would constitute the bulk of the driving narrative language found in manga takes on this form. With that said, these secondary text types described by Unser-Schutz ARE found in Monogatari through the intertitles, and text found in visual structures on screen. As Monogatari does seem to be a collection of stories told by Araragi Koyomi, the asides, and the text found elsewhere act as our authorial comments and create that sense of community between author and reader or in this case, author and viewer. A street sign flashes past that says “no middle-aged men allowed” when Koyomi mentions a particularly disliked character who is middle-aged. When Koyomi and Hachikuji talk about what love is, Koyomi asks where it can be found, and Hachikuji sarcastically says, you can buy it at a corner store for 298 yen. What we also see in this particular image is that on either side of the pile of “Love” kanji are the sold out “first love” and “talent” which are perhaps digs at Koyomi, or perhaps not, but they provide more for the viewer to work with. These quick flashes of additional text are not essential to the understanding the core narrative, but they do help to flesh it out, and establish that deeper connection to the work. Creating "a space of interpretation for dynamic reading, with different readerships [or in this case, viewerships] able to either ignore them, or read them per their needs and desires.

The connections to manga visual language don't stop there, as the intertitles and "secondary text" in Monogatari lead to an altering and adjusting of a viewers' rhythm. Osamu Takeuchi says of the language of manga "language can be used to create a sense of time by differing the amount of text as appropriate to the scene being depicted, thereby developing, altering and adjusting readers' rhythm, through which readers' sense of time also changes as the narrative progresses." And in Monogatari, our secondary text often forces viewers to hit pause in order to properly take in the flashes of text we find on screen. This type of engagement with anime is unconventional—though very on brand for Akiyuki Shinbō—and as such creates an awkward pace for the viewer, if they choose to build that communal relation between author and viewer, and dynamically watch the show. It turns the passivity of watching television into an engaging activity, and by hitting pause to read the intertitles and secondary text the viewer is investing further into the visual language of Monogatari, coming away with a deeper understanding of the grammar and syntax of the visual language presented.

Flip The Script

The final piece of this linguistic puzzle of a show comes by way of the script choices made for text shown on screen. In research done on first person pronoun usage in the manga Usagi Drop, Wesley Robertson found that different characters would use different forms of "I" —ore, boku, watashi & atashi— represented with different scripts —kanji, hiragana, and katakana (which for “ore ” would look like 俺, おれ, and オレ respectively)—and that young male characters showed a preference to "ore " represented with katakana script (オレ). This was a choice made by author Yumi Unita to reinforce the image of "ore " as being "naughty, young, a bit show-offy, visually sharp." Older male characters in her story transition to use the slightly more formal "boku " and often with kanji script (僕). The idea that characters "grow up" through their written language occupies a unique space in Japanese media, and can't quite be as explicitly revealed through spoken Japanese and certainly not in Roman alphabet languages. It gives the reader a subtle hint about the character who uses a particular pronoun and script.

This usage of katakana for young, male characters falls in line with what we see in the intertitles in Monogatari. Koyomi uses katakana for anything that isn't kanji. That is, until we move further along in the chronology of the series. When we arrive at "Owarimonogatari" a story towards the end of the series timeline, we notice something happen to the intertitles. Koyomi, begins to use hiragana in place of katakana. In intertitles presented while on a date with his girlfriend, Senjōgahara Hitagi, Koyomi has shifted from the "naughty, show-offy" katakana, and slips into a more adult mode of language, using the more traditional hiragana characters in between the kanji characters. Though pronounced exactly the same, the change of script shows subtle maturation. Only through text can we make this assertion though, as nothing about Koyomi's cadence or inflection is noticeably different.

The other thing we can glean from the intertitles and secondary text of Monogatari is the choice to use complex and archaic kanji instead of using simpler synonyms that feature more common, everyday kanji or hiragana characters. Much like the showy nature of katakana, and its usage by teenage boys preening for attention, the Otaku community—Japan’s most hardcore anime and manga fans—has embraced the usage of obscure kanji not found in everyday writing, to give their prose flourish, and to show off. While mainstream manga publications strive to match their reader's level of kanji comprehension, perhaps even dipping a little lower to allow more readers in, doujinshi—fanmade comics— crafted by Otaku for the Otaku audience will use unusual kanji or strange readings of those kanji to essentially flex. As Koyomi is our narrator, and is presenting the intertitles and secondary text to the viewer as his own thoughts and worldview, the kanji usage stands out as Otaku-ish, leading the viewer to make assumptions about Koyomi. Take for example this intertitle, which we see when Koyomi and his sister Tsukihi are fighting, which reads gudon na choukei wo shittasuru imouto. This sentence roughly translates to “the little sister who scolds her stupid big brother” but is made up of words that simply aren’t the go-to language for an anime (or everyday Japanese life for that matter). The language is intentionally stuffy and needlessly complex to describe something that could be done so in plain Japanese, without the comically highfalutin kanji characters. There isn't enough space in today’s piece to dig into whether this is simply to identify Koyomi as Otaku, if this is Otaku parody meant to turn the mirror back on the viewer, or if the usage is meant to appeal to the Otaku viewer, but its inclusion nonetheless uses language and script choice to add another textual layer to this work, and add more grammar to the visual language at play.

A Fine Tapestry

Going back to Barthes and Ranciere, these heterogeneous visual elements and the rich visual language of this series are all woven together as part of the "essential fabric" of Monogatari. Textual elements in this anime make a direct connection to established manga visual language, and can act as either a relay or anchorage to lead viewers through the many signifying elements to reach understanding. Working in concert with the oblique camera angles, the head tilts, the inconsistent geography, even the fanservice and the database element characters make up the visual language of this franchise, and only when taken as a whole, when you read full sentences in the grammar and syntax of Monogatari does it begin to elevate the meaning. The elements are familiar to anyone who dabbles in anime, but arranged in just this certain way creates something greater. Individual threads become a tapestry.

Michael Lee is the Editor of KOSATEN, and is currently pursuing research on Japanese fandom, with a particular focus on doujinshi and other fan-created media.