Stuck in Headspace

MICHAEL LEE

OMORI | Omocat

“Games are no longer a pastime, outside or alongside of life. They are now the very form of life, and death, and time itself.”

In her book Gamer Theory, McKenzie Wark imagines a place she calls The Cave™, a business that for all intents and purposes sounds very much like a video game arcade, where gamers meet in a space of pure play to engage with, and compete against, one another. For some, The Cave becomes their reality, spending nearly all their time there, with a few wondering if the world found in their games might have a ‘real’ counterpart out there somewhere. When they leave The Cave, the real world outside ironically is seen as unreal. The ‘real world’ being only a “vast accumulation of commodities and spectacles, of things wrapped in images and images sold as things” while The Cave offers a logical, algorithmic world that has set rules. As cave dwellers look closer, they see that nearly everything in the real world has a gameworld equivalent, and the blurring of what is game and what is not becomes so indistinct that you see a game in literally everything. The only way to escape it, is to return to The Cave and hide completely in the comfort of the video game world. Why not? It’s just as real. Or at least better than whatever is out there.

I was reminded of Wark’s notion of retreating into the Cave as I made my way through the charming indie RPG OMORI. In the game, the player takes on the role of Sunny, a teenage boy who has become somewhat of a recluse because [ReDaCTed fOr sPoiLerS]. Sunny has created an entire world for himself, which is cleverly known as Headspace, and acts as Sunny’s version of The Cave. Headspace is a fantastical world, featuring pastel-colored, dreamy locales with names like Orange Oasis and Snowglobe Mountain.

OMORI | Omocat

Living in a Game

In Headspace, Sunny has created an alternate version of himself, known as Omori, and spends his time in Headspace adventuring with his childhood friends. It operates on the logic of a video game, everything revolves around an understanding of the algorithms at play in the machinic, computational Headspace. Take on a task that a non-playable character asks you to complete, finish the task, receive reward. Fight against monsters, level up, become stronger. Crucially, if the game gets too hard, sends you towards a bad ending, or... gets too close to reality, Headspace can be reset and Omori can go back to the beginning, where his friends are once again waiting for him to start off on their adventure.

Headspace is run like a video game that Sunny can traverse predictably through if he remembers the logic of the game. This is an algorithmic space, where certain variables trigger certain scenarios, and there is no way for an error to crash it. A reset can always give Sunny a fresh start if needed. Because games function like this, they serve as a contrast to our real world, but also create an existential condition as we compare the game world to our real world. Despite video games ostensibly acting as a form of play, a pure leisure activity separate from work and the consequences of the real world, as we look closer at our current reality, we begin to see that the real world has been taken over by gamespace.

OMORI | Omocat

Outside the Cave

When we look closely at gamespace—the idea that gamification has been applied to nearly everything in the real world—from Uber incentives to email management to this app that I’m using to write this piece which is constantly updating my ‘editor score’ as I go— what we find is that everyday life is, in fact, quite imperfect when compared to a game. Nothing in the real world runs as efficiently, or as perfectly, as the algorithmic logic of a game. Even as whole systems in the real world become gamified, it only reveals the imperfections in the way gamification is being deployed, and the way in which we operate as humans in the real world. Wark posits that in theory the game is a logically consistent, coherent and fair system. This contrasts with our gamified reality, where the rules and algorithms we are governed by are in constant flux. They are controlled by actors who seek to drain every bit of engagement, squeeze every dollar, and keep us in a game world with no win condition. Wark’s cave dwellers begin to see the world of a video game as true despite not being real, while ‘reality’ is not true despite being real. Which is the world that we want to live in? One that is clean, but is a fantasy? Or one that is messy, but might actually be real? This is something that Sunny has to grapple with in OMORI.

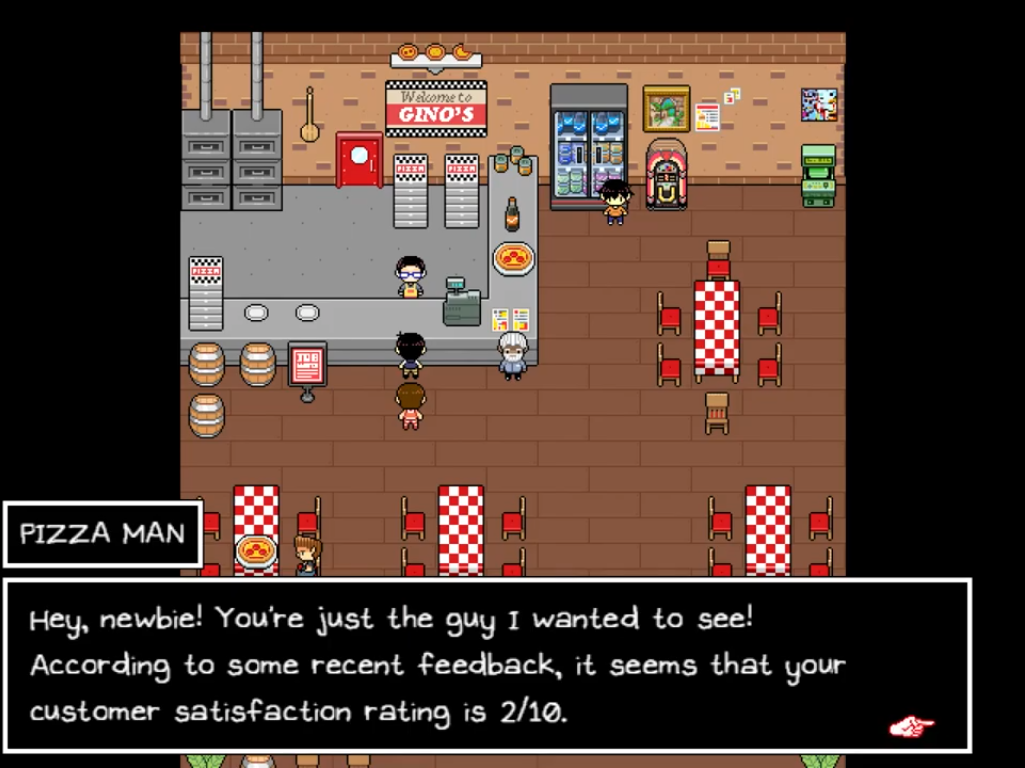

If Sunny chooses to leave Headspace and experience the real world again, the game doesn’t end, he finds that gamespace is everywhere. For dwellers of Wark’s Cave, when they emerge from The Cave they find that everything is a game, every facet of life is a different ‘Cave’ with its own rules and clear conditions. In the context of OMORI, this is exactly what happens to Sunny. Engaging in a fight against a neighborhood bully brings up the same battle mechanics as in Headspace, only things don’t work quite the same. In Headspace, Omori uses a knife to fight. In his fantastical game utopia, play is free from seriousness and morality. Using a knife to fend off the imagined monsters he faces with his friends is well within the logic of the game he is playing in his head. In the real world, Sunny can bring a knife to a fist fight, but if he does, his friends call him out and confiscate it. Yet, Sunny remains silent, giving the player time to wonder if Sunny has fallen completely into gamespace, no longer understanding how the ‘real world’ works. In another instance, Sunny can take a part-time job and deliver pizzas. This too becomes a game. Decipher the handwritten addresses, deliver to the right house, earn a few dollars. Though we as the player understand that we are still playing OMORI, and the video game’s... video game-ness... should continue unabated whether Sunny is in Headspace or in his real world of Faraway Town, when the narrative shifts between the two, we recognize that Sunny’s two worlds bleed into one another. Game and reality aren’t so different to him.

OMORI | Omocat

Gamification Fascination

This is the danger of gamespace, and is something that not only Sunny faces in OMORI, but something we too must face as we navigate capitalist spaces that have corrupted the notion of play. Everywhere in our society we are being influenced by gamification. Work becomes play. Consumption becomes play. Socializing becomes play. Everything we do has to come with a hit of gamespace dopamine to make the mundane seem fun. If you drive for Uber or Lyft, the app never wants you to stop. Rideshare companies incentivize drivers to keep driving in order to reach a certain amount of dollars earned or improve their driver score. The algorithm setting the target just out of reach, but close enough that a driver might pick up an additional fare or two to meet this arbitrary goal. Or consider Amazon, where employees in its warehouses can compete against the clock, and each other, in a number of quota-oriented games. The ‘FC Games’ feature rewards like virtual pets, that may or may not have any actual value, “swag bucks” that can be redeemed for Amazon branded merchandise, and during peak periods, larger prizes are occasionally up for grabs. With gamespace having invaded Amazon, the bastardized notion that work is now play reveals itself to be nothing more than another way to track performance metrics and coerce employees to work harder, because surely they don’t want to lose to the Phoenix #6 Fulfillment Center. Targets are set higher, the carrot dangles elusively out of reach, and employees resort to urinating in bottles instead of taking breaks in order to meet their goals.

Wearable technology tracks steps, and admonishes you for not reaching your fitness goals. Loyalty programs reward customers for repeat business—keep spending, that 10th coffee is free! Dating apps encourage you to participate in limited-time events in order to increase the odds someone sees your profile. War has been gamified, as drone strikes are performed behind computer screens with XBox controllers. Even a Twitch streamer is hit with a barrage of targets, goals, and achievement stickers on their path to becoming a Twitch Partner. The art of playing games has been gamified.

Gamespace is insidious. It twists the utopic space of a game world, changes the algorithm of a supposed fair system, projects it onto anything and everything, and serves the insatiable needs of capitalist structures. The worker who plays in this world can never truly win, as gamespace simply moves the goalposts, delaying gratification in a death drive of repetition and monotony. “Gamespace claims to be the full implementation of a digital Darwinism” according to Wark, “for one and all the rule is survival of the fittest.” Yet, gamespace actually turns this idea into an unadulterated nightmare where the only end point is the “demise of the unfit.” If you can’t cut it, it’s game over for you.

OMORI | Omocat

The Only Way Forward is to Go Back to Headspace

What gamespace ultimately does is lead to a kind of boredom or state of inaction. A spaced-out existence for the player that promises and denies action and leaves one in limbo, wanting to act yet feeling that it will lead to nothing at all. It is the goal of the Military Entertainment Complex to keep the population in this state of inaction so that it can continue to operate its empire unabated. The perpetual engagement through gamification and algorithms is deployed to keep the populace in a state of inaction, yet fooled into thinking this inaction is fun. Games can restore pure action. Creating an urgency to act within a video game reassures the player that doing something is not for nothing. This is what Wark prescribes for us, as we float through a meaningless world of gamespace. Return to The Cave. Return to the game. For Sunny, in OMORI, this is what he must do. Dig deeper into Headspace, play the game to its logical end point, reach the win condition, and having reached the end, leave Headspace and venture back into the real world with a renewed sense of what play is, and what reality is.

In our world, we need to follow the same path as Sunny. Rediscover what a pure state of play is. Seeing the value of leisure completely removed from labor. In doing so, we see how gamespace has infected our current moment, taking advantage of people under the guise of ‘fun’ and creating a neverending malaise. Once we recognize what gamespace is doing, we might be compelled into action to find some version of the real world behind all the flashing lights, prizes, and busted algorithms controlling our everyday existence.

Michael Lee is the Editor of KOSATEN, and is currently pursuing research on Japanese fandom, with a particular focus on doujinshi and other fan-created media.