Gender Identity And A Wandering Son

Michael Lee

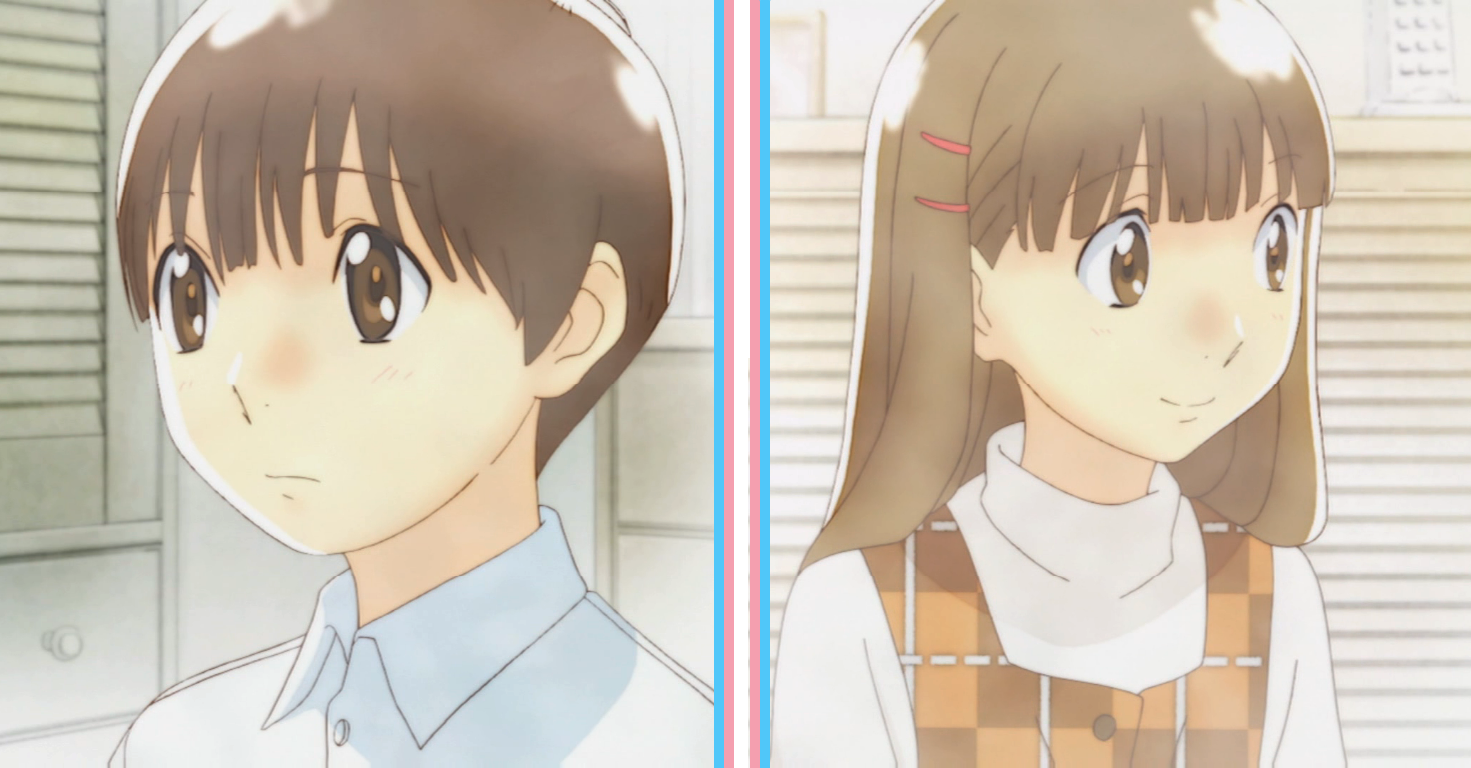

Nitori Shuuichi presenting as male (l) and female (r). | Wandering Son

Anime with queer protagonists (or even queer side characters) is a hard sell in Japan, where LGBTQ+ people fear identifying as such because they worry it may affect their employment opportunities or lead to harassment. And while some local governments have issued ordinances acknowledging same-sex unions, there is no federal legislation allowing same-sex marriage, and the offensive rhetoric of national politicians shows that Japan lags behind in protecting the rights of the LGBTQ+ community. In this context, even subtle changes with regard to representation in anime are important to take note of.

Today we’ll look at the difficulties of being Transgender in Japan through the work Hourou Musuko.

女の子って何でできてる?

onna no ko tte nande dekiteru?

What are girls made up of?

男の子って何でできてる?

otoko no ko tte nande dekiteru?

What are boys made up of?

Nitori Shuuichi asks at the opening and ending of the first episode of the anime Hourou Musuko, [EN: Wandering Son] based on the manga of the same name by Shimura Takako. Nitori poses these questions while trying to make sense of the unshakeable feeling that their physical body doesn't match the gender identity they feel they are as hormones start racing and puberty sets in. This simple nursery rhyme from the 19th Century now carries an immense weight into the 21st Century, presenting a thesis for the series and opening a dialogue on gender identity in Japan with a challenge to the normative views that have left the nation lagging behind on LGBTQ+ rights.

When the story begins, Nitori identifies as male, but as they move into the age where physiology begins to push them more definitively in that direction, Nitori can't help but feel that this is not their identity. The questions start to creep in. How do they want to identify? Will they be able to be their true self? The anime, which aired in 2011, represents one of very few stories in Japan that take an honest look at issues facing transgender people in the country.

Opening to the West, Closing to the Rest

In the Edo Period (1603-1867), Japan was quite open with regard to sexuality and gender identification. Mark McLelland, who has written a range of books and articles on queer sexuality in Japan, notes that "there was no normative connection made between gender and sexual preference..." pointing to a number of male-male relationships that were "governed by a code of ethics described as nanshoku (male eroticism) or shuudo (the way of youths)." Included in these arrangements, McLelland makes mention of transgender males who would work as actors associated with kabuki theater. However, once the country opened up to the West, homosexuality and queerness began to be seen as deviant or abnormal.

Discussion on transgender issues is hard to come by in Japan today, and is mainly confined to the entertainment world. Performers (whether gay, straight, or trans) will cross-dress to present as a different gender. Television personalities like Mitz Mangrove or Matsuko Deluxe or male actors in kabuki who perform Onnagata (the female roles in a Kabuki play) all put on a show. While the performance in Kabuki is rooted in tradition and deeply revered in Japan to this day, television personalities like Mangrove are a ratings sideshow. He laments, "we are not treated as human beings. We are okay as long as we say things that are not mainstream or that are sharp or vulgar," with Mangrove going on to say he wouldn't recommend "ordinary gay people" identify with the outrageous celebrities shown on TV as they might find themselves treated as abnormal too. It's a sad state of affairs if LGBTQ+ members of the entertainment industry, who potentially have influence in the cultural zeitgeist, don't see themselves as fit role models for the community.

"Sugar, spice and everything nice...

that's what girls are made of."

Nitori says halfway through episode one, while out in public presenting as female with a smile on their face. At this stage, only a few close friends know about Nitori's desire to be female, the most important of whom being their best friend Ariga Makoto—a boy who entertains thoughts about his own sexuality and identity— and another close friend, Takatsuki Yoshino, a girl who wants to be a boy. These two support Nitori unconditionally, and Nitori will openly talk to them about their cross-dressing and experimentation with presenting as female. Not everyone sees Nitori's journey the same way, in one episode, their sister Maho walks in on them wearing one of her nightgowns and recoils in shock. She rips the gown off of them, screaming "kimochi warui!" a contextual phrase, but in this case strongly implying that Nitori is "disgusting." Nitori runs from the family apartment out into the moonlit streets, they come across Takatsuki, who immediately stops to comfort Nitori. Debussy's Clair de Lune plays.

The use of Clair de Lune here may seem cliché, considering it turns up in anime quite often, but here its usage is significant. The piece is based on the Paul Verlaine poem, which is a Symbolist piece on the theme of identity and the soul. Verlaine's Clair de Lune is a yearning for one's true self even as we hide that self from view. The "charming masked and costumed figures... sad under their fantastic disguises" reflects the aching that Nitori feels when they wear male clothing. There is a disconnect felt when Nitori cannot simply be their true self, feeling forced to masquerade as male to keep up normative appearances.

That night, a nocturnal emission serves as an irruption into Nitori's life, forcibly reminding them that their biological gender will continue to fight their desire to transition. "Frogs, snails, and puppy-dog tails... that's what boys are made of." Nitori thinks as they stand in front of the family's washing machine. Watching a pair of underwear in the midst of a spin cycle, washing away the evidence of their male biology.

Nitori after running into Takatsuki with the familiar notes of Clair de Lune playing in the background.

The Long Road to Legal Gender Change

In 2004, Japan passed the Gender Identity Disorder Special Cases Act (a name which is already outdated), which allows people to legally change their gender. Unfortunately this piece of legislation contains potentially harmful caveats that have not been addressed in the years since. Human Rights Watch released a report in March of last year that highlights the hardships transgender individuals face, and identifies deficiencies and failings that plague the Japanese system.

In order to begin the process for a legal gender change, the person wishing to transition must be diagnosed as having "gender identity disorder"—yes, the term that is no longer used in most countries. This is something that may be easier in large metropolitan areas like Tokyo or Osaka, but for people in rural areas, could take months or years depending on if the person is able to find a clinic that will make the diagnosis. A person seeking a legal change of their gender must be over the age of 20, unmarried, and not have any children under the age of 20. These rules subtly deny the applicant the right to enjoy a private family life. The final step is to undergo sterilization surgery. This is mandatory whether the individual feels it necessary to their identity or not.

These restrictions pose a great deal of stress for all transgender individuals, but particularly transgender youth, who face a very tight window in which to make life-altering decisions. Many young people fear discrimination should they transition after becoming established in the work force, so must chart their course as soon as they turn 20. This might mean visiting a doctor under their parents' insurance plan, prompting a coming out when the individual may not be ready to do so.

Judith Butler grapples with the question of a GID diagnosis in her book Undoing Gender, where she examines the tension between receiving the diagnosis as a means to an end and the idea of valuing transsexual autonomy above all else. Her work is rooted in the American context wherein the diagnosis can lead to insurance coverage of a "necessary medical procedure" to receive gender reassignment surgery. The Japanese system is structured similarly in that the diagnosis is a first step towards being legally recognized as the gender one chooses to identify as. Is working within the system a necessary evil in order to become who one really is?

Butler argues that "psychological assessment assumes that the diagnosed person is affected by forces he or she does not understand." It pathologizes the person who is seeking treatment to correct an identity they know to be incorrect. There is no lack of understanding present, yet the assessment "assumes there is dillusion or dysphoria in such people... it assumes that certain gendered norms have not been properly embodied, and that an error and a failure have taken place."

Grappling with this decision to play into a system that stigmatizes trans individuals in order to be recognized creates problems regardless of the decision made. Agree to a diagnosis, and be treated as having a disorder, or reject that and never receive legal status as your gender identity. In Japan this means that on all legal documents one’s incorrect gender identity will follow them. And to present differently than that legal identity could invite a host of unwanted questions from officials and people in the community.

Nitori and Takatsuki’s friend, Yuki, who identifies as female (l). She presents as male (r) during one episode.

Nitori and Takatsuki are fortunate enough to have a transgender role model in their lives in the form of Yuki, an adult transgender female who offers the two teens advice from time to time. In a scene that subtly takes aim at the issue of legal identity, Yuki visits Nitori and Takatsuki’s school during the cultural festival—an event where students invite friends and family to the school for a festive open house—but without telling Nitori or Takatsuki, Yuki arrives at the school presenting as male. Though it could be interpreted as Yuki not wanting to be a distraction to Nitori or Takatsuki—who are busy preparing to perform a play—what this choice strongly implies is that Yuki’s legal gender is still male, despite identifying as female. If asked by a school official to present identification, Yuki would be vulnerable, attracting unwanted questions for not appearing to be the gender her identification says she is. To avoid the potential social maelstrom that could result, she presents as male, a decision she shouldn’t have to make when it is clear she identifies as female.

This is the problem with attaching specific medical diagnoses to steps in the process to achieve legally identified status. Individuals are forced to make decisions that could cause social distress. Either in seeking to be diagnosed, or avoiding a diagnosis but running the risk of unwanted questions regarding identity as a result.

Why was I laughed at?

Why was I told this was wrong?

Is Nitori pathologized in Hourou Musuko? Most certainly. By their sister, by classmates, and by the school administration in a scene that pointedly calls out Japanese normative views on gender identity and the exceptional pressure placed on males to retain their masculinity in a phallocentric culture. After witnessing two female classmates don the boys' school uniform with no reprimand, Nitori makes the decision to act on the desire to present as female at school. Arriving at school in the morning Nitori is immediately pulled into the nurse's office—a move commonly employed by school staff to separate an ostracized student, which may only serve to exacerbate feelings of isolation—is spoken to by their homeroom teacher, and promptly sent home.

Their teacher attempts to take blame for allowing the students to perform a gender-bending play and thus “allowing the deviancy” of transgender identity to propagate. The teacher takes no corrective action against the two female students—as of course he shouldn't—but this point bothers Nitori. They wonder why Sarashina and Takatsuki suffer no consequences for their transgression of norms regarding femininity, while Nitori is essentially told that boys don't do this. "Why was I laughed at? Why was I told this was wrong?" Nitori laments. Nitori doesn’t see how they are wrong because presenting as female is who Nitori feels they are meant to be. There is a sureness to Nitori that is admirable. The questions Nitori poses are in response to a society that has made the judgement that Nitori is dysfunctional, when Nitori feels that there is nothing wrong with them.

Nitori (l) presenting as female, Takatsuki (c) wearing the boys’ school uniform, Sarashina (r) wearing a boy’s shirt and tie with her skirt.

This gets to a point that Jack Halberstam brings up in his book Trans* with regard to the need for medical professionals to diagnose a transgender individual as having a mental disorder. For the longest time that diagnosis was exclusively "gender identity disorder" only softening slightly in recent years to "gender dysphoria." As previously mentioned, this diagnosis is essential for Japanese transgender individuals to legally change their gender and thus be seen as legitimate by society. Halberstam's work posits that it may not be an irreconcilable dysphoria that causes mental anguish—as Wandering Son progresses, Nitori becomes more certain of their desire to transition and present as female, with very little “dysphoria”—but the social circumstances are what brings on the anxiety. The backlash against, and pressure put on, Nitori after making the brave step to present as they feel is what causes the dysphoria to seep in.

At the end of the anime, Nitori begins to feel the effects of puberty take hold. Their voice changes, they grow taller, and their face breaks out in pimples; all making Nitori less "cute." Their response to these changes is one of confidence in the face of uncertainty: "I'm fine with this." Nitori is warned that their road ahead may be a challenge, and staying “cute” might be more difficult. They accept this and are determined not to stray from their desire to be recognized as the gender identity they know they are.

Looking back to Halberstam, he talks about the "architecture" of trans* bodies through the work of Lucas Crawford, who employs a "shift from the idea of embodiment being housed in one's flesh to embodiment as a more fluid architectural project" wherein "the body is lived as an archive rather than a dwelling, and architecture is experienced as productive of desire and difference rather than just framing space." While Nitori wants to present as female—wanting to house their identity in female space—the road there may be complex, and instead, Nitori appears open to the idea that the transgender body is the archive, that it is the collection of feelings, actions, behaviors, and support networks that build identity, not simply the physical anatomy.

Halberstam says of his own transition that "the procedure was not about building maleness into my body; it was editing some part of female-ness that currently defined me. I did not think I would awake as a new self, only that some of my bodily contours would shift in ways that gave me a different bodily abode." Nitori's optimism towards their future hints at a view of the self that is less confined to the often prioritized medical view of transgender bodies, and more in line with the archival notion Halberstam and Crawford tease out.

What does the Future Look Like for a Wandering Son?

While Hourou Musuko represents a huge step forward in representation of trans characters and trans narratives in anime, what of Japanese society?

Any country where there are no anti-discrimination laws to protect LGBTQ+ people and litters the path to legal status with roadblocks has work to do. Instead of opting for change, Japan's cultural and political hegemons prefer to stay the course and not disrupt what they see as a balanced, just, and fair society. Introducing the "foreign" concept of transgender identity threatens to upset the balance that places heteronormativity above all else.

However, looking at an international survey of public support for transgender rights, Japanese responses show that more than half of those surveyed support gender change and think trans people should be legally recognized. Only 12 percent of Japanese people believe surgery should be required for legal gender change. Which is extremely low for something that is still law in Japan.

Most telling is that to every question, Japanese respondents had the highest percentage of "Don't Know" responses across the board. What this says is that there isn't enough information about transgender issues available to the public. This is where media can play a crucial role. Stories like Hourou Musuko need to be given more of a push. A-1 Pictures took a chance on Shimura Takako's story about a boy who wants to be a girl, and a girl who wants to be a boy. The studio delivered a faithful adaptation of the source material, bringing the viewer into the world of transgendered youth through the medium of anime. If more works like this can receive similar care and attention, then perhaps Japan’s archaic laws regarding transgender recognition can change.

Michael Lee is the Editor of KOSATEN, and is currently pursuing research on Japanese fandom, with a particular focus on doujinshi and other fan-created media.